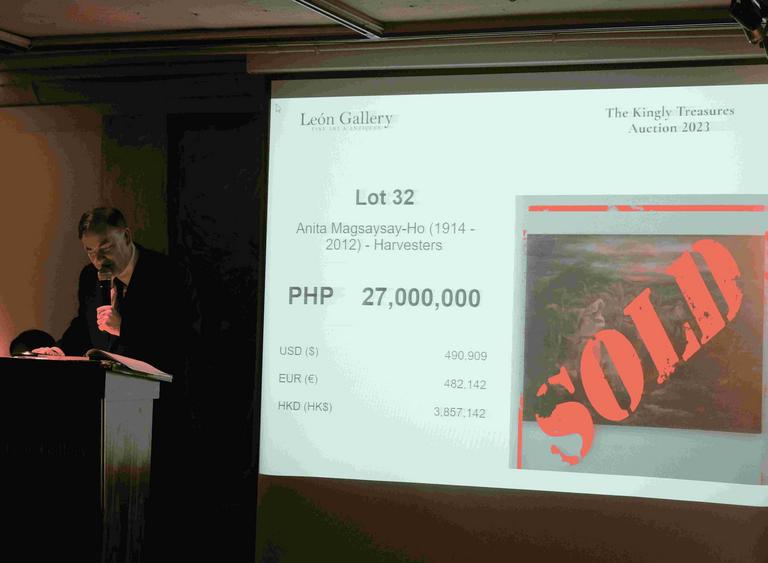

The Philippines’ most trusted auction house. Specialists in culturally important & museum-quality Philippine art and purveyors of fine Philippine antiques and historical objects. We sell a myriad of unique items including Old Master Drawings and Paintings, Modern and Contemporary Art, Furniture, Silver, Rare Books, Maps and Documents, Jewelry, Watches, Rugs and Carpets, Sculptures, Photographs and Ephemera.

Daily 9:00 am–6:00 pm Monday to Saturday

Sundays: Closed or By Special Appointment